Welcome to the Spring 2016 Newsletter from the Kent

Archaeological Field School

WELCOME

BREAKING NEWS: GREAT

CRESTED NEWTS HOLDING

UP DEVELOPMENT

Dear Member, we will be sending a Newsletter

email each quarter to keep you up to date with

BREAKING NEWS/2: LACK OF

TRAINED ARCHAEOLOGiSTS

news and views on what is planned at the Kent

THREATEN PROGRESS OF

Archaeological Field School and what is

DEVELOPMENT

happening on the larger stage of archaeology

BREAKING NEWS/3: OPLONTIS

both in this country and abroad. For more

EXCAVATION ABOUT TO

START

I do hope you enjoy this newsletter which looks

EXCAVATION IN VILLA B

(ABOVE)

forward to a summer of exciting

‘digging’

opportunities. Paul Wilkinson.

BREAKING NEWS/4: NEW

AREAS OF POMPEII NOW

OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

BREAKING NEWS/5: ROMAN

VILLA FOUND IN WILTSHIRE

Breaking News:

RESEARCH NEWS:

Great Crested Newts holding up development

COURSES AT THE KENT

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD

Matt Ridley writing in the London Times says that green bureaucrats cannot

SCHOOL FOR 2016 INCLUDE:

continue to use Great Crested Newts or Bats as a way of stopping useful

KAFS BOOKING FORM

development.

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

Natural England, the government body charged with protecting Britain's wildlife, is

currently consulting on reforming the way protected species are rescued from

bulldozers. The rethink is focused on the great crested newt, the bane of

developers everywhere, and it sensibly suggests giving the newts new ponds so

their populations can expand, rather than the futile gesture of surveying, trapping,

deporting and excluding them from development sites one by one.

This might seem a trivial tale to disturb your bankholiday breakfast with, but don't

be fooled. Newts are big business and very, very controversial. There are about

1,200 licences issued each year to fence newts out of development sites and then

trap those inside and remove them to safety, though they hate being moved and

often don't survive.

Such fencing and trapping directly costs business about £60 million a year. The

actual cost is much higher if you add in the delays that newts regularly cause,

because a developer must trap newts on a development site for at least 30 days

after the newtexclusion fence goes in and then for five clear days of zero catches,

which might take weeks or months to achieve.

Yet, despite this, Natural England is frequently taken to court both domestically and

in Europe by people in the green movement who have too much money and not

enough to do, for not being zealous enough in enforcing the law on newts. Greens

see newts, precisely because they are so common, as a useful weapon to stop

people engaging in economic activity. (I tell you, compared with newty politics,

party politics is tame.) Until recently, Natural England itself was split down the

middle between the pragmatists and the dogmatists. Aided by new DNA,

technoIogy, allowing ponds to be tested for newts without trapping, the pragmatists

may now have the upper hand.

Great crested newts are common. You find them in every part of England, as well

as much of Wales and Scotland. They inhabit Northern Europe as far east as the

Urals, but are scarcer on the continent, which is where these things are decided.

(Yes, we are being punished for success again.) In 1994, Britain implemented a

European directive defining great crested newts as a "European protected

species" (EPSX meaning that you can go to prison for six months for harming them.

This means, because they are so widespread, that housebuilders and other

developers go to great lengths to ensure that any newt living on or near their

development is excluded or rescued so that it is not run over by a bulldozer.

Developers live in terror of breaking this rule. In one case in Milton Keynes, a

house builder incurred £1 million in costs and a year's delay just to remove 150

newts from a site. There's a vigorous industry selling "solutions" to developers.

These include fences lined with heavy plastic sheets partly buried in the ground to

prevent newts entering sites. The fences can be miles in length and are often cruel

barriers to the movement of wildlife. When lapwing mothers are calling plaintively

to their babies that are stuck on the wrong side of a fence, you have to wonder if

we have our priorities right Lapwings are of much more urgent conservation

concern than newts.

The incentives from this policy are perverse. One water company spent tens of

thousands of pounds on newt fencing to keep newts out of a natural habitat No

wonder similar legislation is known in the United States as the "shoot, shovel and

shut up" act. Nothing has done more to alienate businesspeople from wildlife than

this sort of newtystatism.

Suppose, Natural England says, that a minerals company wants to extend a quarry

into what is now farmland, but the extension comes within 200 metres of a newt

infested pond. The pond will not be affected and the farmland is currently useless

for newts, so what's the problem?

Indeed, the quarry extension will turn the farmland into something much more

attractive to newts: with scattered ponds to breed in and heaps of rocks to

hibernate in, so the newt population might rise despite the odd bulldozer accident.

Yet if newts move in, the quarry owner faces a choice between going bust and

going to jail. So he keeps them out.

Natural England's four proposals in the current consultation (which closed last

week) suggest: reducing the need to exclude and relocate newts so long as

compensatory habitat is provided elsewhere; allowing that habitat to be built off

site rather than immediately nearby; allowing newts to use temporary habitats on

site that will be developed at a later date; and reducing the cost of, and need for,

surveys for newts and other EPSs.

All very sensible ideas.

Newts are to be the pioneers, Natural England explicitly hoping that these

measures will also help with other EPSs. In the case of the surveys, Natural

England gives the example of somebody trying to add an extension to a house. To

get planning permission the owner has to do a bat survey. Bat surveys are

expensive and can only be done at certain times of year. If the survey is

inconclusive, you may have to wait another year and get another survey.

The incentive is strong for the bat surveyor to suck his teeth like a costly plumber

and say, as he takeshis fee: "Looks like soprano pipistrelle droppings, squire.

Might be just using it as a day roost, but I can't rule out that they might be

hibernating here too. See you next year."

Instead, suggests Natural England, the house owner should be allowed to go

ahead and build his extension so long as he does the right thing by the bats that

might or might not turn up for hibernation: providing bat boxes, say, and making

sure the work is not started in hibernating season. Common sense, in other words.

But common sense does not always prevail in the countryside.

The green pressure groups, the newtfencing industry and the dogmatists within

officialdom all have vested interest in the current system. The Department of the

Environment even formed a great crested newt "taskforce", boasting (and this is

beyond parody) "several parallel work streams, each involving a committee to

deliberate and progress aspects of policy and capacity".

Meanwhile, British industry is hobbled by a wholly unnecessary source of cost,

delay and uncertainty wearing a yellow waistcoat, a jagged crest and a pointy tail.

Breaking News/2: Lack of trained archaeologists threaten

progress of development

SWAT Archaeology at work in Sholden, Deal UK

Many issues have threatened to derail HS2 and Crossrail2 before so much as a

metre of track has been laid. Cost, route and impact have all been debated

exhaustively. However, the latest potential for delay is also one of the most

unusual: a shortage of archaeologists. With contractors bound by law to fund their

investigations, Duncan Wilson, head of Historic England, has warned that the

number of archaeologists must increase by 25 per cent if supply is to meet

demand. "HS2," he says, "is a transept across the country which, in living memory,

has never been done. It is a real opportunity to learn about that landscape." The

study of history and prehistory does not always march hand in hand with a cutting

edge infrastructure project. In HS2, archaeologists are faced with the enticing

prospect of a 350mile excavation trench, stretching across the country from urban

Victorian London, through rural landscapes unchanged in centuries, to the

industrial midlands. The line passes near Roman villas and medieval villages,

scheduled ancient monuments and a Wars of the Roses battlefield, Edgecote.

English Heritage has said that it is likely that construction of the line will unearth

asyetunknown archaeological remains of national importance.

To do so requires archaeologists, of which there are currently only 3,000. Historic

England is doing valuable work to increase that number, and anticipates a surge in

demand over the next six years. If excavations cannot go ahead, development is

delayed and costs rise.

The time has come for archaeology to shake off its bearded image. Those who

harbour doubts might heed the words of Beattie, the grandmother played by

Maureen Lipman in a 1988 advert for BT. "You get an ology:' she told her

grandson, "you're a scientist!" Archaeologists: scientist or not, your country needs

you.

From the leader in the London Times of May 14th 2016

Breaking News/3: Oplontis excavation about to start

The Oplontis Project began in 2006 with the study of the site known as Oplontis

situated at Torre Annunziata, Italy. The work is sponsored by the Center for the

Study of Ancient Italy at the University of Texas in Austin. Its two directors are John

R. Clarke and Michael L. Thomas. In addition the Kent Archaeological Field

School, Faversham, Kent UK under its director Dr Paul Wilkinson has been

involved in fieldwork at both villa sites since 2008.

The aims of the project are to enable an understanding of the two buildings, one of

which is Villa ‘A’, the other Villa ‘B’ to be enhanced through a comprehensive study

of the buildings, the fabric, the artefacts and human remains, their location, and

their function including a 3d model (above) with interactive database which will

enable scholars to write a series of comprehensive volumes which will be

published by the Humanities eBook series of the American Council of Learned

Societies. The first is scheduled to appear in 2014.

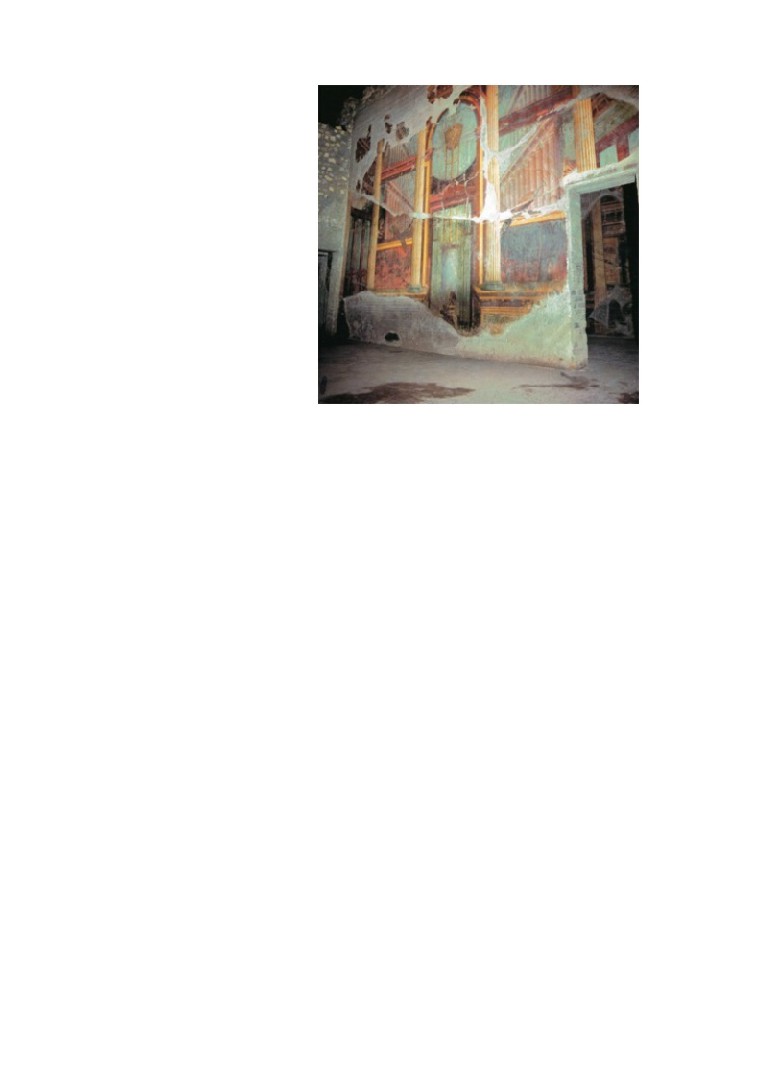

Villa ‘A’ is now recognised as one of the most sumptuous and extravagant Roman

villas overlooking the Bay of Naples. It is thought by many that the villa was the

property of Poppaea Sabina the Younger who was born in Pompeii in AD30 and

married Nero in AD62. The evidence is somewhat circumstantial and consists of

graffiti found on an amphora which said ‘secundo poppaea’ which in translation

means ‘to the second [slave or freedman] of Poppaea’.

The villa was excavated by an Italian team over twenty years ago, and although it

was impossible because of modern development to find the limits of the villa some

99 rooms and spaces were excavated including a sixty metre swimming pool and

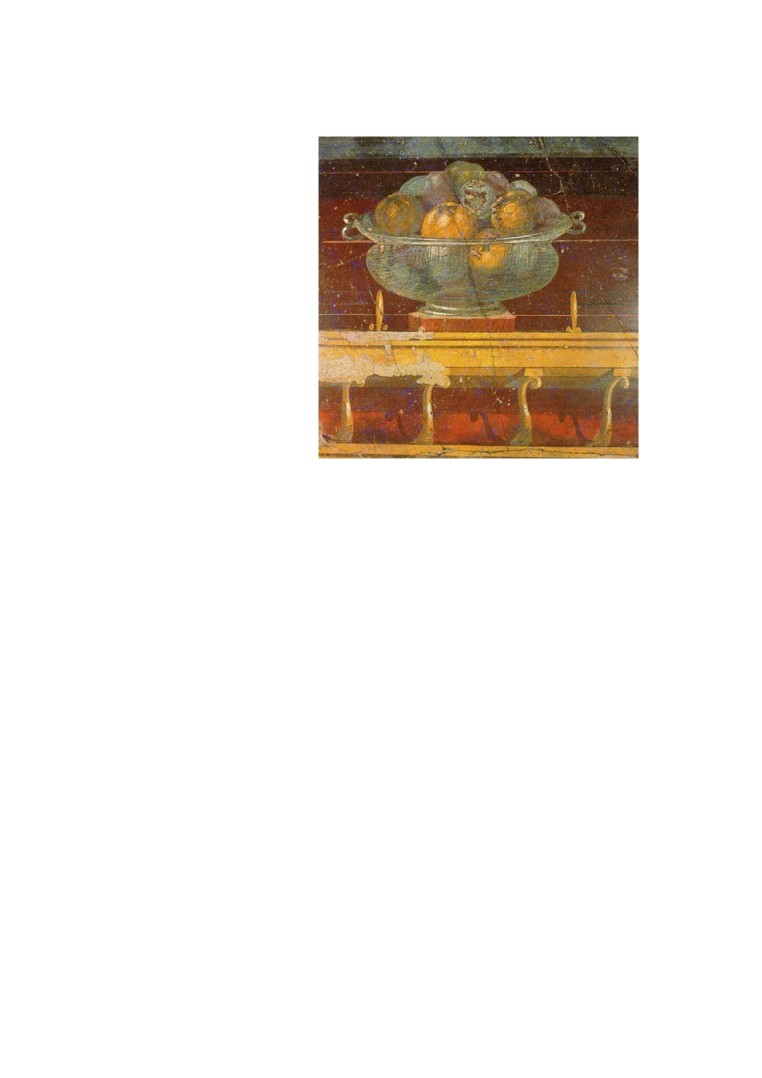

formal gardens. The villa is probably best known for its wonderful Second Style

wall frescoes which can be found in a number of rooms located around the atrium,

itself dating back to about 50BC.

Villa ‘B’ is located about 300 metres to the east of Villa ‘A’ and is not a villa. Its

likely function was a warehouse where wine would be processed and shipped out

in amphorae. Some 400 amphorae still litter the site. Around the warehouse are

roads and streets of town houses still waiting to be excavated.

The plan of the warehouse is focused on a central courtyard surrounded by a two

storey peristyle of Nocera tufa columns. The eastern side of the peristyle includes

an entrance opening onto an unexcavated road running north south and detected

through our coring campaign. Ground floor storage rooms open up into this central

space whilst above on the second floor are residential rooms. To the south lies the

remains of a colonnade and portico and, set back, a series of large barrel vaulted

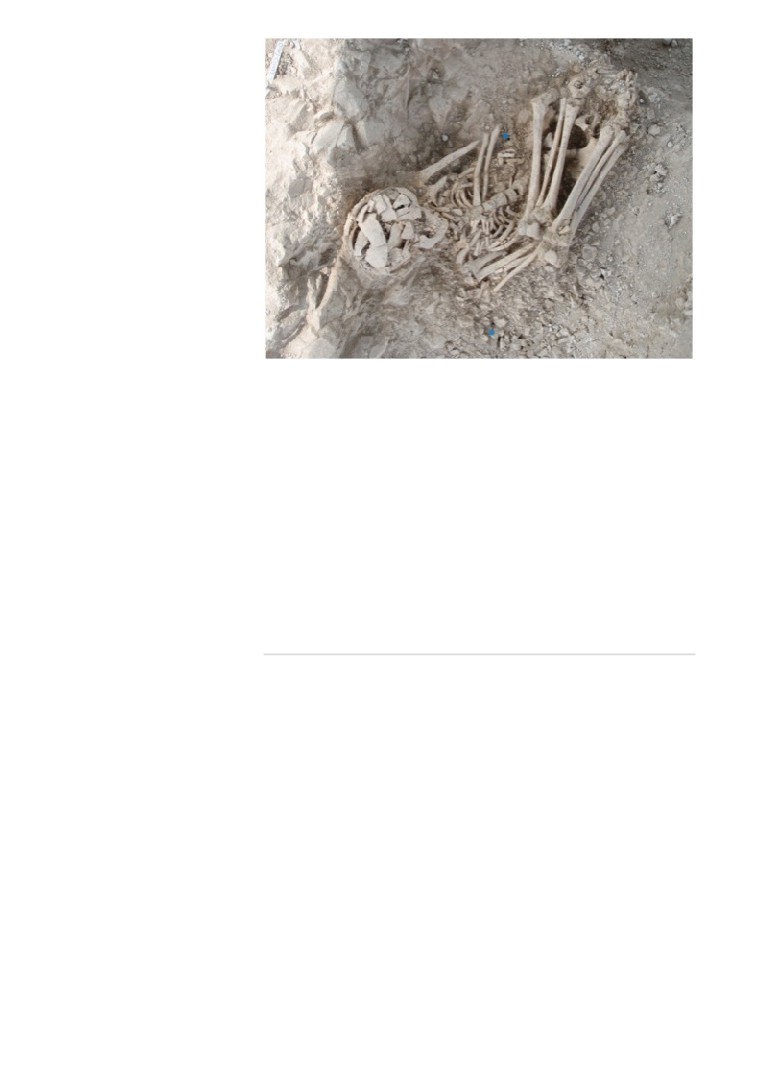

storage rooms which faced the sea. In these rooms, just as in the Roman port area

of Herculaneum, dozens of skeletons were found of people waiting to be rescued

by boat from the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79.

In 2008 I was invited by John Clarke to join the team and started work on site at

Villa ‘A’ helping with a small evaluation trench located in the southern area of the

large swimming pool. One of its aims was to attempt to date the adjacent

foundation wall of Room 78, the large diaeta (private room) to the southwest of the

swimming pool. We excavated through demolition layers of Roman material which

included fragments of exquisite fresco, painted stucco fragments and, the most

wonderful of all, beautiful oil lamps with a variety of designs. To an archaeologist

who normally excavates Roman sites in Britain the quality and quantity of finds

was staggering. The Fourth Style fresco fragments indicated a terminus post quem

date of about 45AD for the construction of the diaeta (above).

The following year I returned to Oplontis with a small team from the Kent

Archaeological Field School (KAFS) and a Landover full of archaeological kit. The

drive from Kent, through France, across the Alps and down the spine of Italy was

memorable and is something I still look forward to every year. In a way it is a drive

through a historic lanscape, and gives one a feel of how extremes and

opportunities of landscape moulded the lives of past peoples. The 2009 season

was busy and eight trenches were excavated at Villa ‘A’. In addition Giovanni Di

Maio who had already undertaken some work on the geological formations below

the villa cored three additional areas to the south of the villa and proved that Villa

‘A’ was situated on a cliff about 13 metres above the Roman sea level. Our work in

2009 included a test pit dug through the northwest corner of the pool. We found

that the pool had originally been larger and had been reduced in width

presumably to allow the colonnade of porticos on the west side to be built. In

addition we excavated part of a circular fountain in Room 20. It had been revealed

by workmen laying cables in 2007 and not recorded. On investigation we found a

partly demolished fountain buried under a metre of demolition debris. The fountain

had quite a pronounced tilt to it which might suggest Villa ‘A’ had been subjected to

serious earthquake damage in the years before AD79. All the piping to the fountain

had been robbed, and in addition a statue which graced the south edge of the

fountain was no longer there, but its concrete ‘footprint’ was!

Another of our trenches was located in the northeast corner of the north gardens

and for once we were digging through layers of pumice deposited by the volcanic

eruption of AD79. Underneath we found an open canal 80cm in width and finished

in coating of cocciopesto (pink waterproof cement), known to archaeologists as

opus signinum. The canal runs north with a slight curve to the east under the

modern car park. The function of the aqueduct fed canal cannot be proved, but it is

likely that it was an open water feature, part of an elaborate garden which went out

of use in antiquity when it was backfilled with earth and debris.

Another garden we looked at was in Room 32, the peristyle in the servants

quarters located to the east of the main atrium. We discovered evidence for an

earlier peristyle that matched the footprint of the later build. The trench produced

copious amounts of marble mosaic flooring, opus signinum slabs, and the

exquisite marble nose from a small statue! The water features investigated in 2009

suggest that the first phase of the villa dated to about 50BC, and was seriously

damaged in the earthquakes of AD62 with the water features decommissioned and

either demolished or backfilled. In 2010 we excavated nine trenches with a view to

unravelling the complexities of the water supply to the villa. In the southeast of the

north gardens we excavated a large cistern with a capacity of about two cubic

metres of water. It seems the cistern, constructed of opus signinum, was to prevent

flooding in this part of the garden, to hold a water supply for the garden, and for

use as a drain to the nearby portico that once lined the eastern side of the north

garden and its adjacent room. The finds from the infill of the cistern were dazzling

with large fragments of a Doric frieze constructed of super fine stucco, two types of

antefixes, and part of a column constructed of wedgeshaped bricks and with

stucco flutes. It was decided to excavate in the centre of the 60m swimming pool

which required crowbars to remove the large basalt blocks which made up the

substructure of the pool. Our daily water consumption went up from two litres a day

in the shade to six litres! The reason for digging was that the ground penetrating

radar had found a significant anomaly underneath the pool foundations.

Unfortunately we did not find any anomaly but we did expose and record the two

phases of pool construction, the eruption layers and the palaeosoils.

Our attention then focused on the area immediately south of the pool. Four

trenches were dug that exposed a portico at the south end of the pool, part of a

wonderful marble floor of opus sectile, a room not recorded before with marble

steps and a Doric column with stucco fluting still in situ. Found on these steps were

copious amounts of pottery and a large piece of marble architrave with part of an

acanthus scroll or volute (opening picture).

Our work at Villa A has gathered additional evidence that after the earthquake of

AD62 large areas of the villa were badly damaged The finding of part of a column

drum from the adjacent east wing in the cistern, the lifting of part of the opus sectile

floor prior to the eruption of AD79, and the remodelling of the swimming pool

suggest that major rebuilding work was being undertaken. The villa also had

problems with its water supply which may suggest that the villa was not habitable

at the time of the eruption in AD79.

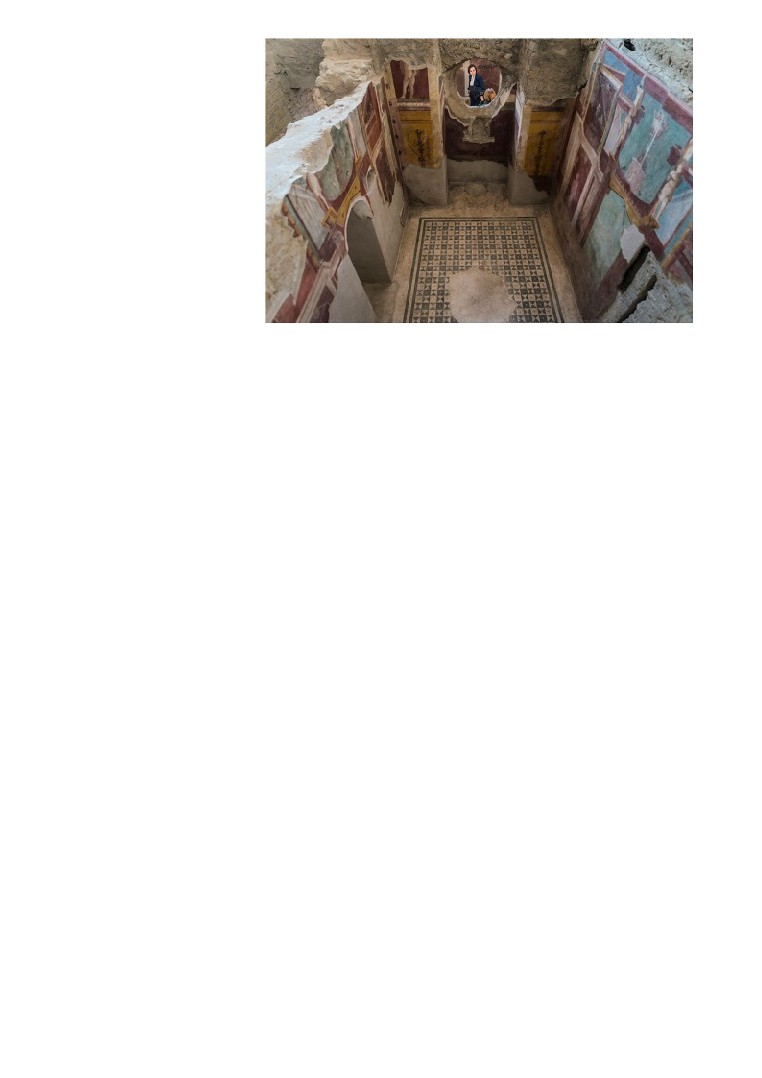

Excavation in Villa B (above)

Initial GPR work had detected a series of anomalies that suggested the presence

of earlier structures under the present exposed buildings. In particular the

investigation suggested that the complex lay just a few metres from the ancient

shoreline. The wider settlement may have been a small town (Oplontis) or a

commercial harbour serving the Pompeian countryside, and will be the first of its

kind discovered in the Bay of Naples area.

Work started in

2012 in the courtyard area with the aim of exposing the

stratigraphy, and to examine the foundations of the building which may produce

evidence of its function and chronology. We expanded the trench to the entire

width of the courtyard and soon had to resort to crowbars as the original surface of

the courtyard comprised large and occasionally very large basalt boulders with the

gaps between boulders infilled with large sherds of amphorae. Some of these still

retained residue which were bagged for analysis.

Immediately under the basalt pavement was the first of many pyroclastic flows, the

first dating to the Late Bronze Age. As we excavated down we exposed and

recorded sequence after sequence of eruption strata and palaeosoils dating as far

back as 15001600BC. Some of these surfaces had carted or sled ruts along with

pottery sherds and remains of mud bricks. The lowest strata were littered with

Bronze Age artefacts, and suggest there was a high level of Bronze Age activity in

the environs of Oplontis B.

Both ends of the trench gave an opportunity to investigate the foundation design of

the colonnade which was unusual to say the least. A thick tufa stylobate sits on top

of foundation blocks (sterobate) spaced to coincide with the joins between the

blocks of the stylobate with the entire assemblage sitting on the same pyroclastic

stratum which we found under the basalt paved courtyard. Sherds of Campania A

Black Gloss pottery found in the foundation trench date the build of this colonnade

to the 2nd century BC.

In 2013 we returned to this area and expanded the trench to expose a complex

water system with a settling tank plus two water channels and various drains. Of

some importance is the fact that this complex water system cut through two

previous floor levels which suggests the function of the building may have

changed through time. Another team undertook the task of removing tons of

modern debris in the area of the south portico. A thankless task undertaken in the

glare of the Italian sun! But well rewarded by exposing layers of volcanic debris

from the eruption of AD79. Underneath this layer we found the original floor

surface with numerous Neronian and Flavian coins. Below that a complex of barrel

vaulted drains was exposed which will need further investigation. Our final

investigation was to examine part of the street north of the main complex. Originally

excavated by the Italian team in the 1980’s, who discovered a street running east

to west lined on both sides with simple town houses on both sides, it is apparent

that these houses have ground floor rooms, some with the foundation step of a

staircase leading to upstairs rooms, and some of which have a simple shrine

dedicated to the household gods. Our investigation showed that some areas of the

ground floor still retained debris from the AD79 eruption and had not been

excavated. Underneath we found a simple beaten earth floor, the step for a

staircase, a toilet and washing area and probably a kitchen area. The road outside

the house was also excavated and showed it had two construction phases which

may correspond to the two identified phases of the adjacent building, the first

probably dating to the 2nd century BC when the building were probably used as

workshops with a wide entrance, and the second phase when the entrance was

narrowed and the building turned into domestic quarters. Indeed, three houses

show walled up entrances, it now became a typical Roman street that included

stone benches outside of each entrance

The last season of excavation will start early June for three weeks and anyone can

join our team. The only criteria is that you are a member of the Kent Archaeological

Field School www.kafs.co.uk and that you have some experience or enthusiasm

for Roman archaeology, Italian food and Italian sunshine! See also the website for

Paul Wilkinson

Breaking News/4: New areas of Pompeii now open to the

public

Tourists in ancient Pompeii have freshly restored marvels to admire, including a

merchant’s luxuriously decorated home and a more modest middleclass dwelling.

A business where Pompeii residents brought fabrics to be cared for and a structure

with thermal bathing areas are also among the six buildings opened to the public

on Thursday after a €105m (£77m) restoration.

In 2008, the Italian government declared a “state of emergency” at the crumbling

site and in 2010 the House of Gladiators collapsed. But a Unesco report in 2012

found little had been done. Pompeii in recent years has been plagued by union

disputes, which left tourists locked out, and the collapse of some ruins, with a

chronic shortage of funds for maintenance.

But the Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, expressed optimism at the unveiling of

restored ruins in the city destroyed in AD79 by a volcanic eruption. He said: “We

made news with the collapses, now we are making news with restoration.”

One of the most eagerly anticipated restorations is of the Fullonica di Stephanus, a

specially designed laundry equipped with large baths for rinsing dirty tunics and

basins for dyeing fabrics. There was a press for ironing and a place to store urine,

which was collected in public toilets and used to get out tough stains. Clothes

would be trampled by workers in tubs at the back of the premises.

The Guardian

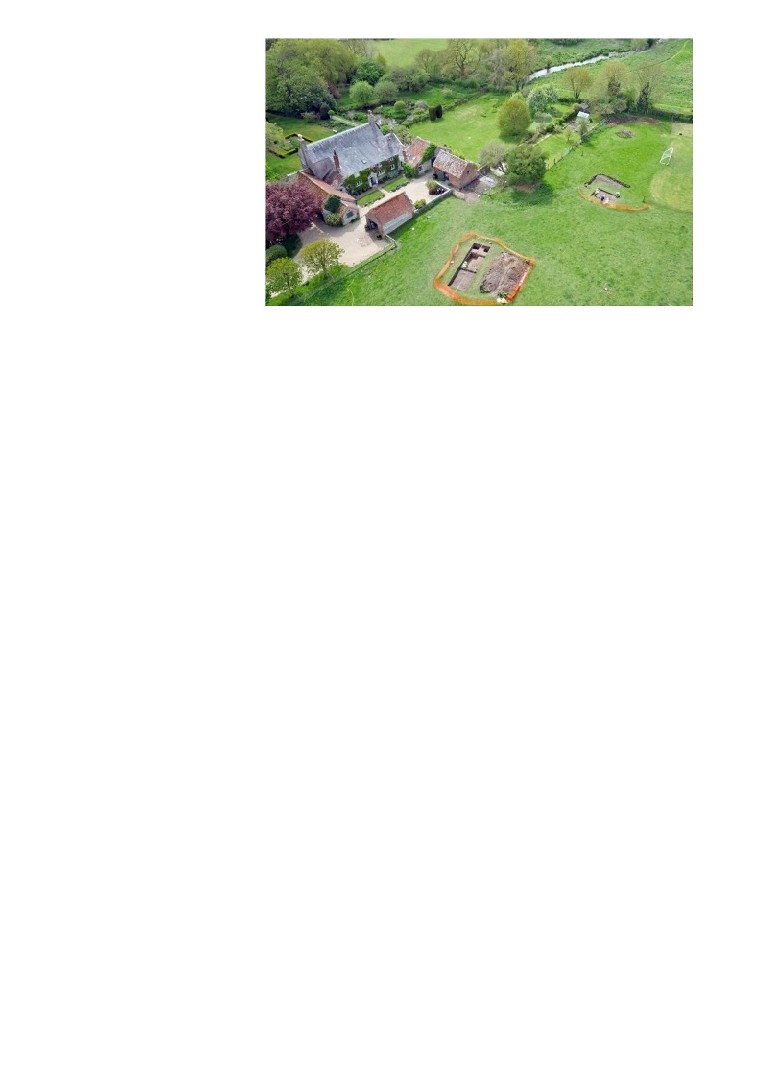

Breaking News/5: Roman villa found in Wiltshire

It started off as a bit of basic home improvement, but it ended up with the discovery

of one of the largest Roman Villas ever found in the UK.

While laying an electricity cable beneath the grounds of his home, near the village

of Tisbury, in Wiltshire, Luke Irwin found the remains of what appeared to be an

ornate Roman Mosaic.

But what emerged when archaeologists from Historic England and Salisbury

Museum began excavating the site was even more of a surprise.

They found the mosaic was part of the floor of a much larger Roman property,

similar in size and structure to the great Roman villa at Chedworth.

But in a move that will surprise many, the remains - some of the most important to

be found in decades have now been reburied, as Historic England cannot afford

to fully excavate and preserve such an extensive site.

Dr David Roberts, archaeologist for Historic England, said: “This site has not been

touched since its collapse

1400 years ago and, as such, is of enormous

importance. Without question, this is a hugely valuable site in terms of research,

with incredible potential.

“The discovery of such an elaborate and extraordinarily wellpreserved villa,

undamaged by agriculture for over 1500 years, is unparalleled in recent years.

Overall, the excellent preservation, large scale and complexity of this site present a

unique opportunity to understand Roman and postRoman Britain.”

Excavations at the site revealed a large Roman property, similar in size and

structure to Chedworth

He added: “Unfortunately, it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to fully

excavate and the preserve the site, which cannot be done with the current

pressures.

“We would very much like to go back and carry out more digs to further our

understanding of the site. But it’s a question of raising the money and taking our

time, because as with all archaeological work there is the risk of destroying the

very thing you seek to uncover.”

Mr Irwin, a Dublinborn designer who makes handmade silk, wool and cashmere

rugs, made the fortunate find last summer while laying electricity cables beneath a

stretch of ground to the rear of his property, so that his children could play table

tennis under lighting in an old barn.

His builders had barely begun to dig a trench for the cables when they hit

something solid, just 18 inches below the surface.

On closer inspection it appeared to be a section of a Roman mosaic in remarkably

good condition.

Intrigued, Mr Irwin called in experts from the Wiltshire Archaeology Service,

Historic England (formerly English Heritage) and nearby Salisbury Museum.

Further exploratory excavation of the site now known as the Deverill Villa after the

name of Mr Irwin’s 17th century house - revealed surviving sections of walls, one

and a half metres in height, confirming that the mosaic formed part of a grand villa,

thought to have been threestoreys in height, its grounds extending over 100

metres in width and length.

It is thought the villa, which had around 20 to 25 rooms on the ground floor alone,

was built sometime between 175 AD and 220 AD, and was repeatedly remodelled

right up until the mid 4th century.

The remains at Deverill are similar to those found at Chedworth, in

Gloucestershire, suggesting that the building belonged to a family of significant

wealth and importance.

Chedworth was built as a dwelling around three sides of a courtyard, with a fine

mosaic floor, as well as two separate bathing suites - one for dampheat and one

for dryheat.

The villa was discovered in 1864, and it was excavated and put on display soon

afterwards. It was acquired by the National Trust in 1924.

The discovery at Mr Irwin’s home also revealed a number of fascinating objects

from the Roman period.

Among the artefacts discovered during the excavations were a perfectly preserved

Roman well, underfloor heating pipes and the stone coffin of a Roman child.

Another was the stone coffin of a Roman child, which had long been used by the

inhabitants of the adjoining house as a flower pot, most recently for geraniums.

Archaeologists believe that during the postRoman period timber structures were

erected within the ruins of the onceornate villa.

They say further research of what was found at Deverill would throw light on what

remains one of the least understood periods of British history between fall of the

Roman Empire and the completion of Saxon domination in the 7th century.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, one of Britain’s leading historians said: "This remarkable

Roman villa, with its baths and mosaics uncovered by chance, is a large, important

and very exciting discovery that reveals so much about the luxurious lifestyle of a

rich Romano British family at the height of the empire.

“It is an amazing thought that so much has survived almost two millennia."

Mr Irwin was inspired by his discovery to create a series of rugs based around the

theme of the Roman mosaic he unearthed. His collection will be put on display at

his showroom in central London, in May.

He said: “When I held some of the tessaras, the mosaic tiles that were found, in the

palm of my hand, the history of the place felt tangible, like an electric shock. The

brilliance of their colours was just extraordinary, especially as they have been

buried for so long.

“To think that someone lived on this site 1,500 years ago is almost overwhelming.

You look out at an empty field from your front door, and yet centuries ago one of the

biggest homes in all of Britain at the time was standing there.”

But while the artefacts have been removed and are now in the care of Salisbury

Museum, the remains of the villa and its mosaics have been reburied and grassed

over to protect them from the elements.

To expose and preserve the mosaics and fragments of walls would be prohibitively

expensive and beyond the budget of Salisbury Museum. Even if it was financially

possible, Mr Irwin does not want his garden turned into an openair museum.

So the villa at Deverill, found after so many years, has been lost from sight once

again, awaiting future generations

Zeeya Merali Smithsonian Magazine

Research News: Aerial survey of Kent. Paul Wilkinson reports on a research

project by the Kent Archaeological Field School

‘If you are studying the development of the landscape in an area, almost any air

photograph is likely to contain a useful piece of information’

(Interpreting the Landscape from the Air, Mick Aston, 2002).

Students of the KAFS have started a two year programme of collating Google Earth

aerial photographs from 1940 to 2013 to enable focused information which can

then be followed up by ground survey. The fruitfulness of this can be appreciated

by the work of the field school along Watling Street in North Kent where hundreds

of important archaeological sites have been identified. The ultimate aim is to

publish the results online. Aerial photography is one of the most important remote

sensing tools available to archaeologists.

Other remote sensing devices that will be used are satellite imagery and

geophysics. All of this information can be combined and processed through

computers, and the methodology is known as Geographic Information Systems

(GIS).

A news story of last year was the discovery of WWI practise trenches in an area to

the west of Gosport at Browndown, A place the writer knows well as a small boy he

lived nearby and played in the very same trenches. A replica World War One

battlefield where soldiers trained in trench warfare before being sent to the front

has been discovered in Hampshire.

Two sets of opposing trench systems, with a no man's land between them, were

found beneath heathland at the Ministry of Defence's Browndown site in Gosport.

Gosport Council's conservation officer Rob Harper spotted the trenches on a

1950s aerial photograph recently. Armed forces volunteers are now helping to

map and record the battlefield site.The size of 17 football pitches, each trench

system had a 200m long (660ft) front line, supply trenches and dug outs.

Describing his discovery, Mr Harper, said: "I was looking for something else. I was

looking for Second World War pillboxes and features associated with an airfield

nearby and I came across this 1951 plan in the office of this area in Gosport.

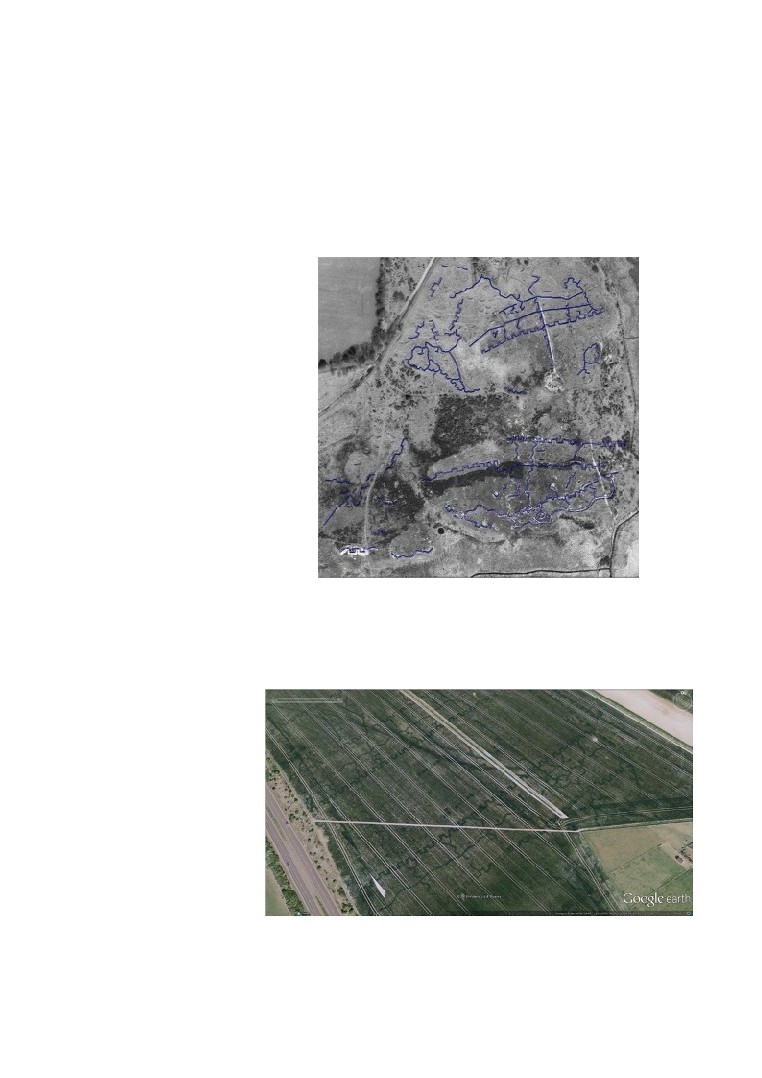

Now research by students of the Kent Archaeological Field School (below) has

found much better evidence in Kent. To the east of the Roman Dover road and to

the south of Bridge can be seen

Adjacent to the WWI trenches and to the north and south the Roman road from

Dover to Canterbury can be easily seen with the road dividing.

To continue to Richborough, and the other branch to Dover. The road passes

through a Roman roadside settlement just south of Eastry.

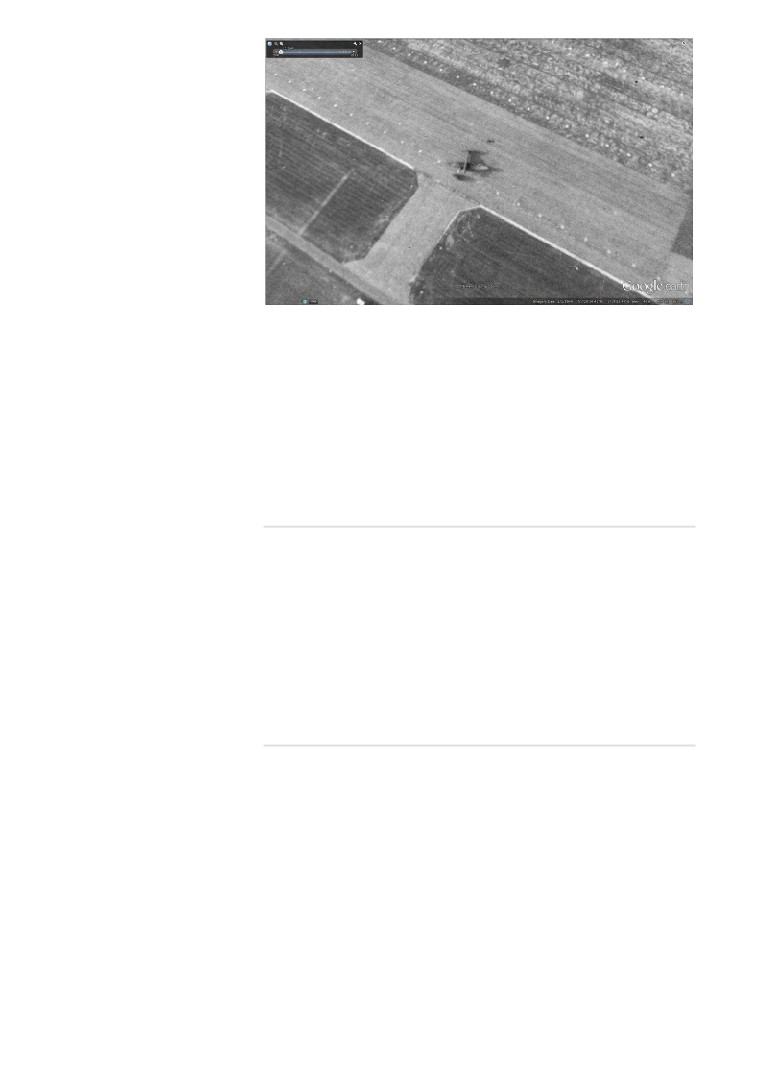

The

1940 Google Earth aerial photographs are a rich resource for WWII

researchers and the picture above shows a Spitfire about to take off at Manston.

Courses at the Kent Archaeological Field School for 2016

include:

May 30th to June 17th 2016 excavating at 'Villa B' at Oplontis next to Pompeii in

Italy

We will be spending three weeks in association with the University of Texas

investigating the Roman Emporium (Villa B) at Oplontis next to Pompeii. The site

offers a unique opportunity to dig on iconic World Heritage Site in Italy and is a

wonderful once in a lifetime opportunity.

August 6th to 14th 2016. The Investigation of a substantial Roman Building at

Abbey Barns in Faversham

Ongoing excavations at a previously unrecorded Roman building in Kent have

uncovered evidence of an emporium serving the port at Faversham - then called

Durolevum.

Discovered in 2012 by the Kent Archaeological Field School (see CA 261), recent

work has shown that the waters of the Swale estuary lapped the buildings, which

during the Roman period sat beside a large tidal inlet deep enough to harbour

ships.

Current work on the complex’s bathhouse has yielded prestigious small finds

including silver jewellery, exotic glass vessels and large quantities of coloured wall

plaster which, together with the structure’s impressive dimensions, measuring

some 45m by 15m, suggests a building of some importance.

A silver finger ring found in the demolition rubble has been dated to the Anglo

Saxon period and similar rings found at Dover have a date of c. 575625 AD. The

ring, only big enough for a child’s hand suggests the building was demolished in

the late 6th century to make a platform for a timber hall found in last year’s

excavation. Pottery in the cill beam slots dated this building also to the 6th century.

KAFS director Dr Paul Wilkinson says the latest findings suggest it had rather

humbler origins, however.

‘The building was originally built in the 2nd century AD as an aisled barn with a

concrete and chalk floor,’ he said. ‘We have found the remains of stalls used to

house farm animals in the Roman estate. But very soon afterwards the building

was rebuilt as a huge bathhouse, with plunge pools, hot rooms, steam rooms, and

warm rooms for massage.’

‘The decoration has the feel of a municipal baths with none of the luxurious

features one would expect of a private enterprise bathhouse,’ he added. ‘Given the

size of the bathhouse it is far too large for a Roman villa estate and must have

catered for another set of clientele. It is probably too far from the main Roman road

to London (Watling Street) to have been an Imperial posting house with hotel but it

probably sits astride the Roman port of Faversham and may have catered for the

crews of visiting ships.’

Pottery from the site has been dated by Malcolm Lyne which indicates the building

continued in use to the late 4th century and into the early Saxon period being

demolished in the 12th century. ‘Latest investigations have unravelled some of the

mystery of the building’s function but this work is still ongoing,’ Wilkinson said.

‘Field walking has indicated there are other Roman buildings alongside the inlet

and future investigation

- including geophysical survey - will focus on their

chronology and function.’ Cost is £25 a day for non member and free to members.

Membership is from £15 per year see www.kafs.co.uk for membership details.

August 8th to August 12th 2016 Training Week for Students at the Roman,

Faversham in Kent

It is essential that anyone thinking of digging on an archaeological site is trained in

the procedures used in professional archaeology. Dr Paul Wilkinson, author of the

best selling "Archaeology" book and Director of the dig, will spend five days

explaining to participants the methods used in modern archaeology. A typical

training day will be classroom theory in the morning (at the Field School) followed

by excavation at the Roman villa.

Topics taught each day are:

Monday 8th August: Why dig?

Tuesday 9th August: Excavation Techniques

Wednesday 10th August: Site Survey

Thursday 11th August: Archaeological Recording

Friday 7th August: Pottery identification

Saturday and Sunday (free) digging with the team

A free PDF copy of "Archaeology" 3rd Edition will be given to participants. Cost for

the course is £100 if membership is taken out at the time of booking. Nonmembers

£175. The day starts at 10am and finishes at 4.30pm. For directions to the Field

School see 'Where ' on this website

September

3rd to

11th

2016. Investigation of Prehistoric features at

Hollingbourne in Kent

An opportunity to participate in excavating and recording prehistoric features in the

landscape. The week is to be spent in excavating Bronze and Iron Age features

located with aerial photography and Geophysical survey. Cost is £25 a day for non

members and free to members.

Pottery from Hollingbourne excavations so far

Overall, 205 sherds weighing 3kgs.593gms were the recovered during this trial

excavation. Only two periods are represented with a predominant essentially

EarlyMid Iron Age presence (201 sherds) from Area 2 and a rather uncertainly

dated one, but probably Early Medieval (4 sherds), from Area 1. The latter are from

the same vessel and made using a rather coarse quartzsand clay containing

probably naturallyoccurring sparse flint inclusions. With such a small sample

further research into a likely source is backburnered - however its general fabric

type is broadly in keeping with other recognised contemporary fabric types from

the eastern part of the region. Its firing colour could suggest a later twelfthearlier

thirteenth century production date, rather than earlier.

The EarlyMid Iron Age component

The recovered total is fairly small - however the frequently moderatefairly large

sherd size, the presence of several intercontext samevessel equations between

Contexts 019 and 026, together with the generally only moderately or slightly worn

condition, all indicates that most sherdassemblages are derived from undisturbed

contemporary contexts.

In terms of fabric types there are two main deliberatelyadded ingredients

-

crushed flint represented by the majority and one vessel with a mixed, flintand

organic, tempering. However at least 3 main clay types were recorded - non

sandy, clays with a varying quartzsand and greensand component and purely

greensand with/without sparse quartz. All three clay types occasionally had

additional inclusions of both ironstone and probable fossil shell. The ironstone

component occurs as both hard fragments and softer ‘rotting’ iron oxides. The

relative rarity of these inclusions suggests either different sources from the ones

principally used or, perhaps more probably, they represent only sporadically

occurring redeposited elements. All three main clay types were used for the

coarsewares but the basically pure greensand clay type appears to have been

principally favoured for the production of fineware vessels - probably because the

dense fine greensandy matrix with mostly fairly sparse fine flint tempering allowed

for the application of a good quality smooth burnished finish.

In terms of form, decoration and finishing types - the sample is fairly small but, as

recovered, coarsewares predominate. Amongst the latter, most elements are from

jars with highset mostly angular shoulders mostly below distinctly curving necks

and everted rims - although in one case the shoulder angleconcave neck profile

is so weak as to be virtually nonexistent. There are also several deep bowl forms

with high rounded shoulders and simple rims. Finishes are rather roughandready

but reasonably competent with, externally, vertical or diagonal fluted finger

smoothed rustication below shoulders and light horizontal smoothing above. A few

bodysherds have a light rather more slurried type of rustication. Interiors finishes

consists of rather minimal varidirectioned smoothing. Two samevessel jar

bodysherds from Context 026 have a more deliberately decorative finish of,

apparently, continuous fine vertical combing. One large jar element from 026 has

its rim decorated with shallow cablestyle finger presses and its neck hollow

unusually decorated with a set of randomly horizontal small stabbed dash

impressions. Finewares are mostly represented by plain body, angular shoulder or

base sherds with fairly light but even and adequate burnishes. One small scrap

from Context 021 has traces of a probable combed chevron design. Two rims, both

from 019 - one fineware class, one subfineware, are rather less mundane and

from smalldiameter bowls or possibly cups with upright profiles tapering inward

slightly towards the base. Both share the same trend for a flattopped rim with a

markedly beaded inner lip.

In terms of parallels and dating the combed finish on the coarseware sherds from

026 is a fairly typical component of a number of unpublished Kentish EarlyMid

Iron Age assemblages - particularly those from the eastern part of the region. It

occurs on coarsewares from a number of contemporary northern French sites eg

NeuvillesurEscaut and FontaineNotreDame, both in the Department Nord, and

Duisans, PasdeCalais (Hurtrelle 1990, 18, 23, 56 and 64). Neuville and Duisans

were dated to c.500450 BC and FontaineNotreDame to 450400 BC. It has also

been recorded from a western Kentish settlement at Cuxton, dated to the Middle

Iron Age, c.400200 BC, (eg. Morris 2006, Fig. 3.8a). The range of jar and bowl

forms available are broadly paralleled from the EarlyMid Iron Age assemblages at

White Horse Stone (Morris op.cit. Fig.3.7d) and Highstead, Chislet (Couldrey 2007,

Period 3B) - both placeable between 600400 BC. This dating could also be

applied to the little cups or small bowls from with prominentlymoulded inner lips

from 019 which are reminiscent of a neatlymade cup from Highstead Period 3B

with straight flaring sides.

There is an apparent absence from Hollingbourne of any fineware bowls with

complexmoulded shoulders - both recorded from Neuville and White Horse Stone

- and more likely to date between c.600500 or 450 BC than later (pers.comm.

Peter Couldrey). As a result it is currently felt that this little assemblage should

postdate the sixth century BC. The quoted Mid Iron Age parallel for the comb

finished elements could indicate a similar date here. However not only is the

present material definitely not like MIAtype forms of third century date (ie between

c.300200 BC and possibly from c.350 BC) but also the forms from Cuxton, despite

their

400200 BC dating, is much more in keeping with EMIA material. The

implication is that there is an interstyle transition period, arguably datable to

between c.400350 BC. With the latter likelihood in mind - and lacking a more

diagnostic range of forms it is felt the present assemblage from Hollingbourne is

initially best placed to between c.500350 BC.

Nigel MacPhersonGrant

The Kent Archaeological Field School, School Farm Oast,

Graveney Road, Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP

Director Dr Paul Wilkinson

KAFS BOOKING FORM

You can download the KAFS booking form for all of our forthcoming courses

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

You can download the KAFS membership form directly from our website, or by

If you would like to be removed from the KAFS mailing list please do so by clicking here